Fear and Loathing in Cabrini-Green: The Dangers of Cultural Appropriation in Candyman (1992)

Candyman (1992) has been in the news of late, thanks to the announced remake coming in 2020 from Jordan Peele. The original was written and directed by Bernard Rose, based off Clive Barker’s short story, “The Forbidden,” from one of his Books of Book installments. The DNA of the story has remained consistent: woman seeks to document local urban legend and summons the vengeful spirit to her own detriment. People are seriously excited to see Peele’s take on the subject matter – I know I certainly am, for a reason that many have expressed all over social media: as a white woman seeking to understand perspectives outside of my own, I want to see a black filmmaker take on this story so that I can learn more from a different perspective I have not experienced. Articulating this further, I feel that a major point of the first film gets overlooked in favor of the gentrification theme: the entire mess of summoning the Candyman (Tony Todd) has its roots in white grad student Helen (Virginia Madsen) trying to take a story that belongs to another culture and use it for her own purposes without truly seeking to understand it.

Backing up a bit, one of the main points of criticism, rightfully, is the look at gentrification in this film. The theme comes to us from the original short story, which sees the character Helen investigating the graffiti of a rundown part of town (based in Liverpool, England, and lacking the distinct racial overtones of the film) for her graduate thesis; Helen starts poking around and finally meets the Candyman, who claims her as his latest victim. The film elaborates a bit more on that, placing the action in the notorious Cabrini-Green housing project of Chicago – a place known for its crime and racial stereotypes – that saw an increase in upscale high-rises in the 1990s, further highlighting socio-economic gaps. Between Mayor Byrne’s publicity stunt to prove the area crime-ridden and the push to make the area a mixed-income (read: massive economic gap that pushes out the poor) section of town, the place came to symbolize the struggle to improve living quarters without the residents getting pushed out and further fucked over. There’s no one that personifies that tone-deaf approach to a problem more than Helen, a well-heeled graduate student who strolls into the projects to get the inside scoop on a local legend so that she can write the best thesis in her department.

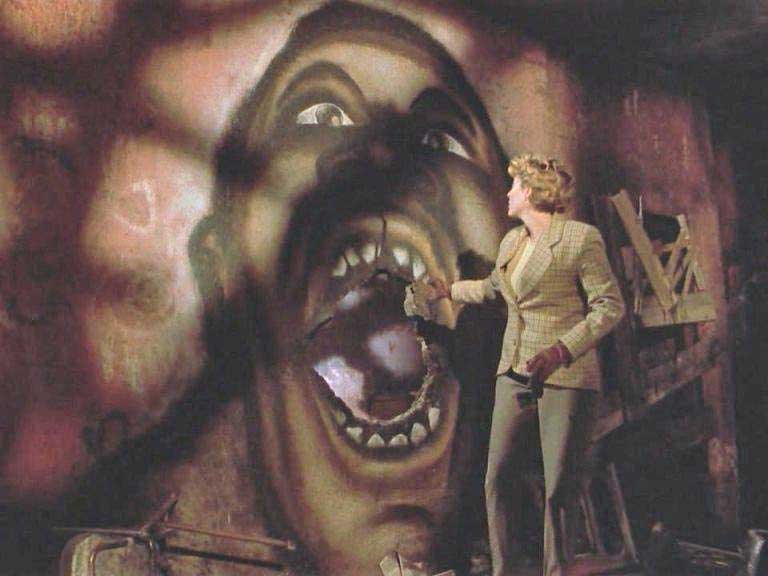

Here’s where it gets problematic: the Helen of the film doesn’t perform her research out of a desire to help the community have a voice for the influx of crime and the further victimization caused by socio-economic disparity. Helen wants a thesis that’s not like every other thesis out there: she wants to capitalize on the story of people she insinuates as less educated and brightly-futured than she. Helen tells her hesitant friend of the project, “we can write a nice little boring thesis regurgitating all the usual crap about urban legend. We’ve got a real shot here… An entire community starts attributing the daily horrors of their lives to a mythical figure.” Helen doesn’t believe for a second that there could be something behind the story, as most folklore is rooted in an explanation of a traumatic event; to her, the residents use the Candyman as an excuse for why things are bad for them and nothing beyond that excuse, which includes mutilations and murders. Helen isn’t in this for the plight of the residents – she wants a thesis that is going to make her look good, that’s going to set her apart from other students, that’s going to snare her a great job offer and academic accolades. She doesn’t want to listen when a child tells her about another kid who was castrated by the Candyman. She doesn’t listen to the desperation and distrust of Anne-Marie (Vanessa A. Williams), who implores, “What you gonna study? How we’re bad? We steal? We gang-bang? We’re ALL on drugs right?… We ain’t all like them assholes downstairs, you know. I just wanna raise my child good.” She doesn’t listen to the blatant statement, “White people never come ’round here except to cause us a problem.” Helen keeps going, even when she’s assaulted, because she thinks she’s got a good lead on a thesis that could bring her professional glory. She’s thinking about being hailed as an original for relaying the legend that grew out of a man being lynched for having the audacity to achieve financial success and a sexual relationship with a white woman while being black. Helen does not give a shit about the realities of poverty for the people of Cabrini-Green, not their concerns, their stories or their safety until a baby gets kidnapped and she gets blamed for its assumed death. While some may argue that she sacrifices herself for the baby to live in the end, the audience is left with two distinct pieces of evidence that contradict this heroic action: she dies with a clear name – that she was not a murderer – and she carries on as part of the legend by killing her adulterous husband. Helen isn’t a folk hero – she’s an opportunist thirsty for attention and the need to be right.

That is where the film makes a stunning point: Helen takes a story that belongs to the black community and seeks to use it for her own gain without really paying much attention to what it means to the keepers of the tale. That’s the definition of cultural appropriation right there: she borrows without thinking of the cultural significance for the express purpose of meeting her own needs and desires, which falls squarely into the territory of unthinking exploitation rather than dissemination of information and tradition. She essentially waives the concerns of the community members, some of whom are extremely hesitant to speak with her on several different levels: the nature of the lynching story involving white aggressors tormenting a black man; Helen’s socioeconomic and education differences, marking her as distant and separate from the daily realities and experiences of the community; the need to only intervene when she herself is in danger of being perceived as an evildoer. Helen wants the story without delving into the true histories and concerns – she can always walk away from Cabrini-Green while everyone else must keep on living there with the literal boogeyman stalking their bathroom mirrors. She doesn’t have to get in the mind frame of the urban warrior to survive because she can go back to her cozy apartment and write a thesis that will procure a respected position in academia, all while her colleagues applaud her for having the courage to walk around a bad part of town to write a glorified term paper. If she had listened to the stories she studied, she would have realized the levels of racial and socioeconomic distrust reflected in the tale’s history and themes – she could have made someone’s life better by bringing attention to issues that desperately needed correction. Instead, she cherry-picked and exploited local lore, then complained when her safety was threatened for being treated like an outsider trying to take advantage of a community’s hardships. She’s the white savior figure that falls flat on her face because she can’t make an effective difference by using her platform to do something good for the group – she merely exploits, then whines when the piper calls to be paid.

The takeaway from Candyman in 1992 is the need to allow people of color to tell their own stories. Don’t swoop in and tell those stories for them – let them have that voice, because the perspectives brought differ in ways that can educate in areas we sorely need. So often, the voices and perspectives of artists of color are shut out. And so I leave you with a reading list – here are some excellent writers of color who deserve to be read; it’s time we listen.

http://www.graveyardshiftsisters.com/