Oh Not You Too: The Abuse in Overboard

There comes a point where you realize that a movie you loved really had some terrible themes going on. Internally, you can hear the glass shattering as your world comes crashing down. I liken it to the realization that Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer” was not, as thought by the little girl version of me that used to sing it when it came on the radio, about a dude hitting things with a hammer ala Gallagher (go ahead and laugh at that one; I’ve earned it. You can even picture me looking completely horrified as a teenager, mouth slack and eyes wide. It wasn’t a pretty day.). We’ve all had those moments. The older I get, the more the hits keep on comin’. Most recently, it was the shattering of 1987’s Overboard by fellow writer Rebecca Booth.

Shoes on a boat: far more terrifying than snakes on a plane.

Rebecca pointed out that the love story in Overboard is, at best, abusive. “No way,” my brain scoffed. After all, I loved this comedy. It’s a great story about a wealthy woman named Joanna (Goldie Hawn, laying on the rich bitch realness) with amnesia that gets her comeuppance from Dean (Kurt Russell), the carpenter she stiffed. With the help of his rambunctious sons, Dean knocks her down a couple of pegs to understand his world; in the process, they fall in love, his sons get a mother they so desperately need, and the life they forge is more appreciative and authentic. Cue the music. Rebecca was not having any of that, insisting I take another look at it because it contained elements of abuse.

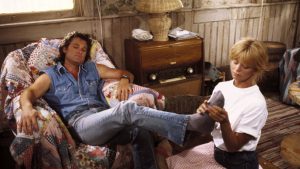

What’s so nefarious about a foot rub?

So I looked at it. Is Joanna a bitch? Oh absolutely. She’s a complete asshole; we’re thrilled to death when she eats a bug and has to redo her manicure on her yacht. We’re crushed when she pitches Dean’s tools into the water and stiffs him on the bill, because even then we can see that he’s struggling to make ends meet. She’s biting in her insults, and as a result, we greatly dislike Joanna. It’s funny when she loses her memory, and when her husband considers himself free of the misery of being married to her. Dean decides to let her work off the debt of his tools and labor, choosing petty revenge in a way that only Russell can make charming. However, upon closer inspection… the comeuppance bears a close resemblence to gaslighting, which is never justifable. Dean refers to her as “a wonderful slave” while singing a made-up song to the tune of “Zipadee Doo Dah” after the woman has experienced her first full day of physical labor in a house that would make even a seasoned cleaning staff recoil, she’s left to sleep on a couch with rowdy dogs, then given a list of more chores to do. As the film progresses, she forms emotional attachments to children she believes are biologically hers, and embarks on a sexual relationship with a man she’s been told is her husband. The scary part? She’s told this stuff. She doesn’t remember it because she can’t remember it. It’s not that she has Stockholm syndrome and adapts as a way to cope; there’s no conscious abandonment of her previous life, either through kidnapping or sale. This woman can’t remember a thing about herself, from her name to whether or not she was ever pregnant with the four children she’s told are hers. Everyone around her is in on the joke, and they feel entitled to be nasty to someone who has no recollection of her crimes.

Accurate representation of me in the kitchen.

Shit. Rebecca was right.

Look, I hate people. I really hate people. I hate assholes, especially those that think it’s okay to mistreat someone who doesn’t make as much money as they do. I cheered along with the yacht staff when Dean tore Joanna down for being the classist asshole she is. However, stepping back from the situation, the “punishment” is just as wrong. Gaslighting someone who has a traumatic brain injury is a special level of sick. It goes above and beyond the parameters of decency. While there are funny parts to this movie, the joy gets sucked out of you once you realize what’s going on. And really, once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Just like that, the glass shatters and you’re left wondering how to put the mirror back together again. Unfortunately, you can now see every fracture; it’s up to you if you decide that you can still look at it, and if you can stomach what’s reflected back.

Really, aren’t nifty sunglasses and Roddy giving you a pedicure indicators of living the dream?

At some point, I’m sure I’ll be able to go back and revisit this film. Parts of it will still be funny. But the experience will be far more muted now. There will be that pall cast over it because I’ve found the gray spot in another clear day. The choice is to either keep laughing despite my better sense of social justice and horror, or shake my head and acknowledge that something is terribly wrong. Either way, it’s not an easy experience.