“We Don’t Need Yours”: The Problem with Forgiveness in Suspiria (2018)

** Warning: This post containers spoilers for a film still relatively new. **

Upfront: while at first distrustful of the updated Suspiria (2018), I came to love it over the course of its two-and-a-half-hour runtime. Luca Guadagnino clearly studied the styles and themes of 1970s Italian cinema, in everything from the colour schemes to the giallo trademarks to the political undertones. The film has taken, at the time of writing, a good month to stew over, simply due to the sheer layers I’ve wanted to digest; truthfully, this post was very nearly about the political themes and their ties to the film, which will be covered at a later date. For now, though, the focus rests upon the implications of a brief exchange between Susie (Dakota Johnson, who was damn fabulous) and Dr. Klemperer (Tilda Swinton as Lutz Ebersdorf) concerning his role in her coup of the dance academy and her broad gesture of forgiveness.

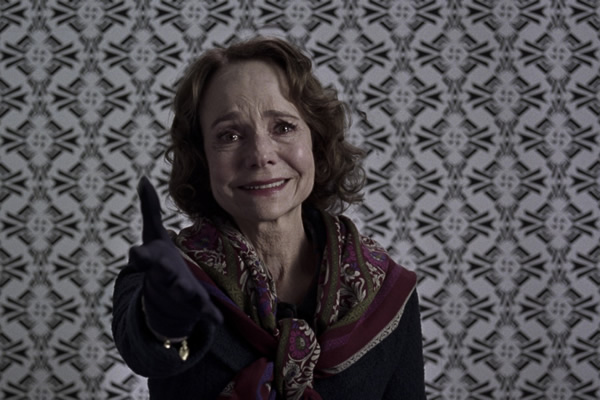

The scene comes at the tail end of the film: Klemperer, traumatized and bedridden, recovers from his ordeal in the bowels of the dance academy, where Susie has revealed herself to be the true Mother Suspiriorum and dispatched the other witches faithful to Madame Markos. Klemperer – a man continually searching for his missing wife, Anke (Jessica Harper) – had previously attempted to help troubled ballerina Patricia (Chloë Grace Moretz), then sought out the assistance of academy member Sara (Mia Goth), inadvertently causing Sara’s torture and death. Mother Suspiriorum reveals to him that Anke – who had wanted to leave a bad situation in Germany long before her husband did – was captured by Nazis and taken to a concentration camp, where she died of exposure during a cruel exercise by her sadistic tormentors. Mother Suspiriorum tells him, “We need guilt, Doctor. And shame. But not yours,” before wiping his memories, giving him some peace before his death.

Except one of the larger problems with this blanket forgiveness comes from the troubled nature of Klemperer’s actions both during the present setting of the film and before the action even takes place. During the climax of the film, Klemperer was lured to the academy by a conjured version of Anke, then berated by other witches for his gender bias of his patients. Miss Huller (Reneé Soutendjijk) screams at him, “When women tell you the truth, you don’t pity them! You tell them they have delusions!” Previously, Klemperer had stated “a delusion is lies that tell truth” when discussing Patricia’s seemingly psychotic ramblings; however, that was merely his perception of the therapy sessions. Ol’ Patty was right on the money with what she had suspected and experienced, and yet Klemperer had viewed her as not perceiving the world around her accurately – according to him, she may have seen some stuff that she interpreted and spun into her own strange version of events, but she was an unreliable source of information because clearly that couldn’t have happened. This line of thought works to validate his hypotheses resulting from his experience rather than believe the suffering woman in front of him. If this had been a one-off instance, we could justify getting behind Klemperer as the voice of reason in a world gone to complete supernatural chaos… but the problem is that this is slyly established as a pattern for him, as Miss Huller points out. Earlier in the film, when discussing Anke, he mentioned that she had wanted to leave Germany long before the Nazis came for the couple; he, on the other hand, patronized her by telling his worried wife that she had nothing to worry about – they had papers, and besides, it wouldn’t come to that. So when the piper came a-calling, Anke was hauled off; I’m noting here tentatively that we don’t know if Klemperer himself did time in a concentration camp. Either way, though, Anke pays for her husband’s flippant dismissal of her concerns and anxiety, choosing instead to let his hubris ultimately lead to her anguished death. This past action parallels his disbelief of Patricia, then of Sara’s concerns; he needs to physically witness Sara dancing on a broken leg and screaming in pain once the magic wears off to confirm that something might actually be there with these outlandish accusations and suspicions. He can’t take a woman’s word for it – he’s got to do his own investigation and witness the pain of someone else for it to be real; even then, it’s got to be something he physically perceives as accurate before accepting it as the truth.

And Mother Suspiriorum thinks that he deserves forgiveness for that, because he was stripped naked, mocked, and forced to watch a supernatural coup as the corrupt, dishonest leader of a coven was ousted alongside her loyal cronies.

The place where this leads us is one that holds a vast amount of discomfort, because we have to ask ourselves, At what point should we forgive someone? When has penance been satisfactorily achieved? And really, that’s a hell of a loaded question to pose at this point in time considering the mass unveiling of women (and men, and children) stating that they’ve been wronged. When do we get to accept apologies – when the rage dies down? When someone makes an effort to do a little digging and validate claims of abuse? When one person is saved from a bad fate? Does one action really erase established patterns of behavior that have harmed people? Do we have the power to forgive someone for actions that have stretched beyond our scope of experience? Is this a major disrespect to someone who has been silenced and abused – possibly even killed – as a result of someone’s bullheaded need to be right? Was this even Mother Suspiriorum’s place to offer this type of plea deal?

I’m inclined to think not, and here’s why: in my college years, I had the opportunity to meet several Holocaust survivors as part of a course on Holocaust literature, and one of the main themes and discussion points was forgiveness. Their views on the subject greatly shaped my own understanding of the act of forgiving someone. One spoke of how she had forgiven her tormentors because she had no desire to hurt herself further – anger and hatred, she felt, were prices she would have to pay, not those who had harmed her and her family. Another – a gentleman who had to relearn how to eat and walk after liberation, who went into the camps at the age of 12 and didn’t come out for three years – steadfastly denied forgiveness, stating that his tormentors deserved whatever punishment they had coming to them, whether in this life or the next, and they earned every stick of his fury. Neither of these people were wrong, because their trauma could not be erased by others, nor is it the place of someone else to grant forgiveness for them. While there are merits to both viewpoints – peaceful existence versus justified anger – forgiveness cannot be viewed as a blanket healthy cure so that life can continue. The individual gets to decide; we mustn’t take that from them as well.

Socially, we like to forgive to move on, to cleanly compartmentalize the troublesome parts of life so that there’s harmony and happiness moving forward. There’s often a pressure to do so from outside sources, with a myriad of nuances in between that range from the need to continue working with someone versus the establishment of a harmonious family dynamic versus a need for the guilty party to repent and go to sleep at night. There’s no easy answer to the question, Should I forgive this person? The answer lies within the wronged party, and so if you’re not the person who has to live with the repercussions of someone else’s actions, leave the forgiving to the person who does. Sometimes, it’s not up to you.