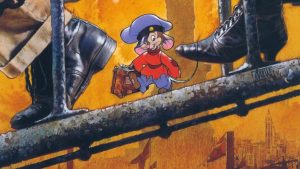

And the Streets Are Filled With Cheese: The Relevance of An American Tail (1986)

Upfront confession: I am not a fan of Don Bluth’s catalog of work, as I find him cloying and too cutesy. However, as my college mentor once told me, “Just because you don’t like something doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have value.” As much as I continue to hate to admit it, he’s onto something (grudgingly, thank you, Greg). I’m not the biggest fan of Bluth’s An American Tail (1986), but given recent events, we need to talk about this one.

Keep skipping, kid.

An American Tail follows Fievel Mousekewitz, a cute-as-a-button mouse who lives with his parents and siblings in Russia. Fievel’s family decides to head to America after a bad incident (more on that in a minute), as they firmly believe “there are no cats in America and the streets are filled with cheese” (good luck getting that out of your head). Along the way, Fievel is thrown overboard from the ship upon which he’s traveling; he miraculously survives and winds up on the shores of America, then is taken under the wings of kind strangers. Believing him dead, his devastated family tries to carry on, all while their son attempts to find them. Several songs and a community-filled stand against cats later, he’s reunited with his family. Swell of heartwarming music, and exit the feeling in the glow of family togetherness.

Family togetherness.

Except that we need to look more closely at the very specific plot points of this story. Fievel isn’t just Russian – his family is Jewish to boot. In fact, the inciting moment that facilitates the move to America comes from an antisemitic attack: the Mousekewitz family lives in the home of the Moskowitz family, which is burnt down in a Cossack attack, prompting flight to America. On top of that, once Fievel is in America, he’s sold to a sweatshop for cheap child labor. His parents wallow in depression at the loss of their child, despite that their daughter Tanya insists he’s still alive. Meanwhile, a mouse named Bridget – from Ireland – helps rouse the other mice to fight against the cats, and uses her connections to an alcoholic politician mouse to find this kid’s family. That is a lot to pack into an animated film directed at children.

I cannot even.

Except that here we are, 32 years later, and the themes in this film matter so much right now. Children are still separated from their parents at the U.S. boarder – people who have attempted to flee horrific conditions like religious and political persecution, where the system has failed them, and they only want asylum so that they’re not killed. The whole idea of the American dream still stands for those who are trying to escape Hell: in America, there’s supposedly a chance to outrun all that ails you, to prosper in a place where there’s more justice and opportunity, from safe drinking water to an education to a better roof over your head – as bad as it might be, trust me, it’s better than what they’ve fled. The rose-colored glasses optimism is present in this film as desperate families daydream of how everything is perfect in America, a place which we then see houses problems such as poverty and exploitation. Then add the layer of anti-Semitism: in my current location, our local Jewish center has reported a serious uptick in violence and threats. Not to mention the fact that in Pittsburgh, a fucking synagogue was shot up recently, killing 11 people. There’s an armed militia making its way to the border to intimidate already-scared women and children. We can claim that we’re more enlightened, yet this film has aged incredibly well – and that should terrify us. In 1986, a film was produced that addressed the horrendous circumstances of fleeing one’s homeland through the eyes of a scared kid, the hyper-idealism of immigration in the face of said flight, the sorrow of familial separation, the seedy underbelly of city life, and the need to take a stand against an oppressive group making life difficult for entire communities. In 32 years, this film holds as much water, and that is not right. We shouldn’t be looking back and saying that things are still the same; we shouldn’t look at a film that’s over three decades old and recognize that fucking nothing has changed. We should be looking back and saying, “Kids, there was a time when this rang true, but it’s a better world now. No one bombs you if you’re Jewish, and we’re all more tolerant of people who are escaping really bad situations.” We’ve learned nothing, and human rights should not be stalled out in an animated film from the 1980s that criticized the treatment of immigrants.

The cats here suck, kid.

I want to write a snappy conclusion to this, but I can’t. I can’t make a joke about this film and what it presents to us. It’s too raw and too relevant. So what I implore you to do, dear reader, is to go back to this film, then look ahead. In another 32 years, do we still want to say that persecution that forces people to uproot their lives only to have them shattered is alright? Do we still want our country closed off to someone who is desperate and wants to live? Because that’s what we need to ask, and we need to figure out how we’re going to look at ourselves in the mirror after we’ve made our decisions.