Conformists: Belonging and Isolation in The Thing

Some people hate the winter time. I view it as a time of appreciation: I get the chance to stop and be thankful that I’ve got a roof over my head, food in my belly, and a warm blanket and couch (and a Netflix subscription, because essentials). This means that it’s perfect weather for horror movies, some of which take place in the snowiest conditions, including two of the best: The Shining and 1982’s version of The Thing. In particular, The Thing gives us a chance to examine social acceptance versus the necessity of containment in order to ensure global survival. In essence, this film pits the need to cooperate and belong against a firm sense of isolation.

Yeah, winter will totally drive you to this.

The need to connect to others is apparent from the film’s start, carrying through until the end. Right from the beginning, we see MacReady (Kurt Russell) keeping himself amused through computerized chess. It’s worth noting that he’s been drinking and takes the chance to pour his drink into the computer when he feels it can’t be beaten, signifying a need for human contact as opposed to the cold imitation of it. Nauls (T. K. Carter) delights in wisecracking and jettisoning around the base on his roller skates, particularly demonstrating a love of music (who doesn’t love Stevie Wonder?) while annoying Bennings (Peter Maloney) by refusing to turn it down. Palmer (David Clennon) and Childs (Keith David) smoke pot and watch porn together. Windows (Thomas Waites) is in charge of getting in touch with the outside world, a task at which he notes he has not been able to accomplish for a few weeks. This is a group of men on a expedition in the Antarctic; they only have themselves for companionship and entertainment. We get early on that they need each other mentally as well as physically in order to survive. Hence we get the relationships between them: the little annoyances, the small rituals, the coping mechanisms. It makes sense that MacReady is boardering on alcoholism and Clark (Richard Masur) is so attached to his dogs – they need these things in order to keep themselves sane and move forward.

May not be the cutest thing ever, but it’s *your* dog.

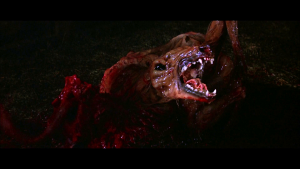

So when Blair (Wilford Brimley) begins calculating the probable chance of infection, he must make the call to isolate them in order to prevent a global catastrophe. Blair renders that there’s a 75% chance that “one or more team members may be infected by [the] intruder organism,” and “if [the] intruder organism reaches civilized areas [the] entire world population [will be] infected 27,000 hours from first contact.” In doing that math, that’s a little over three years to destroy all life on earth through cheap copy. The words used are telling: the organism is referred to as an “intruder” that “infects” its hosts by “imitation” and “assimilation.” In fact, during his autotopsy of the lifeform that resulted from the dog, he explains it as, “It immitates other life forms, and it immitates them perfectly. When this thing attacked our dogs, it tried to digest them, absorb them… We got to it before it had time to finish.” This is something that does not belong: it’s an outsider without benefit, that has the potential to corrupt and destroy all life on earth. As such, Blair destroys parts of the chopper and kills the dogs to ensure the team’s isolation. His thinking is spot-on: keep it contained in order to prevent a larger disaster. Considering that his autotopsy most likely resulted in his infection, this proves to be a self-sacrificing act before he totally loses himself.

I’m an ass but I’m going to do it anyway: diabetes.

This is where The Thing gets genius in its approach to the need for isolation in the face of the very human instinct to be social. The thing needs to fit in by copying the DNA of something else, effectively absorbing it in order to pass completely; however, this absorption does not mean that it’s readily accepted. A prime example of this is demonstrated with zero dialogue: the introduction of the thing in dog form into the pen of animals. The dog lies down amongst its supposed peers, but does not put its head down to sleep as the others do. Instead, the thing watches the others, who in turn sense that it’s not like them. The response? The thing attacks the other dogs, spraying them and wrapping its appendages around them, pulling them into its body in order to consume it and become more like it. This is a forced social and biological acceptance: if the dogs can’t welcome the thing into its folds through kindness and emotion, the thing is going to force the process in order to ensure not only its survival, but domination in the food chain. This is echoed in MacReady’s ostracization from the group and distrust of others: once he is suspected of not belonging, he’s literally left out in the cold. While MacReady confides in Fuchs (Joel Polis) concerning moving forward, even Fuchs starts to settle on the notion of cutting off contact with others, suggesting that the team begin preparing their own means, and suggesting only eating out of cans. In order to ensure that the human race survives, the team must isolate themselves from each other and the rest of the world. They have to go against their natures – the need to make connections, trust others, and work as a team – in the name of the greater good. It’s asking someone to act inhuman in order to save humanity.

Torch him.

In one of the most telling scenes of the film, MacReady sits at the tape recorder, documenting the ordeal for whomever will find it. At one point, he states, “Nobody trusts anybody anymore.” However, he erases it. Was this out of a sense of guilt? A sense that someone may use it to declare wrongly that he is a thing? Or is it because he knows that he will need to rely upon the others in order to survive? It’s up to the viewer to make the interpretation as to whether MacReady is making one last stab at remaining human and connected or inching toward the disconnect that is necessary to prevent the fall of the world.