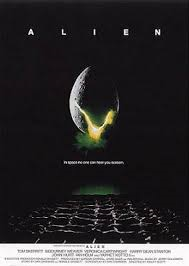

The Corporation: Bad Big Business in Alien

One of the many reasons I love Ridley Scott’s 1979 masterpiece Alien stems from the fact that it takes care of what many consider to be “the haunted house problem” – that notion of oh, I don’t know, leaving the haunted house rather than staying there to face terror and certain death. In Alien, you can’t leave that haunted house and its horrors because you need it to survive the cold darkness of space. There’s nowhere to run and hide. You’re left alone, completely dependent upon that ship and what it represents in order to make it home safe. It becomes your home, your parent, your life support system. In the 1970s, companies were a lot like that: you had people that had worked for 30 years at the same place, effectively making the workplace a family. These people had been with you throughout the good and the bad: they gave you a cigar when a new baby was born, they baked casseroles when your mother died, and they celebrated everything from birthdays to retirements with you. In essence, these people were your family. You trusted them. And that makes what Alien represents that much more horrifying for the 1970s audience in this context: the notion that something your trust with your life is going to allow and encourage actions that will lead to your violation and painful death in the name of turning a profit.

The ultimate symbol of corporate America.

From the offset, this group displays an intimacy that stems from their close working quarters. The first time we see their ship, the Nostromo, it’s empty and lifeless, with machines piloting it. Our first shot of the crew? They’re waking up from hypersleep. Better yet, this group sleeps like most of us: in our underwear, which means that the transparency they have goes all the way to their lack of clothing. Our next shots of them are telling as well: we get the group eating and smoking at the communal table. The camera moves fluidly in a circle as we first meet them, with no head at the table to establish a hierarchy. Yes, there is rank, but not at this table – this is where they come to eat, joke, and smoke. There’s teasing with this bunch, as well as other signs of domesticity, including the presence of a cat named Jones. It comes as no surprise, then, that there’s tension when Kane (John Hurt) is attacked by the face hugger. Dallas (Tom Skerritt) and Lambert (Veronica Cartwright) want to bring him on board, but Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) wants to follow protocol to keep everyone onboard the ship safe. Both have good intentions: Ripley wants to keep the group safe, while Dallas and Lambert want to save Kane’s life, insisting that he may not survive if they follow protocol. You don’t do that for someone who is just a coworker, someone you don’t care about personally. There’s universal relief when the face hugger falls off of Kane. What does the crew do? They celebrate with a meal. A meal that has jokes about food when Kane starts choking. A choking incident that turns into valid concern when Kane begins to convulse. An incident that leaves the group in shock and horror when the chest burster appears.

Plain and simple, the company has sold them out. The ship’s computer, MUTHR, wakes them for a transmission by an unidentified lifeform. The group has concern that it’s an SOS distress call; at the insistence of Ash (Ian Holm), they follow the imperative that all intelligent life must be investigated. This is the inciting incident that sets them on their pathway to corporate betrayal: the establishment of protocol/rules, then the enforcement by Ash, who functions as a type of diabolical double agent. Dallas isn’t exactly trustful of the company, explaining his misgivings to Ripley as, “Standard procedure is to do whatever the hell they tell you to do.” He’s willing to accept this as part of the cost of earning a living; Ripley, however, is concerned about the group’s personal safety, demonstrating that life matters more than profit. She’s right to question this, and so it’s fitting that she’s the one to learn from MUTHR the mission: “Insure return of organism for analysis. All other considerations secondary. Crew expendable.” Her response is to burst into tears, which we understand. She’s just been told that her life does not matter after she has witnessed colleagues and friends dying brutally at the hands of a lifeforce without conscience or moral code. She gets to be a meal, and that’s just fine by her employers. Nevermind that she’s out in space, away from her family and friends. She has to give her physical life because the company tells her to do so.

Thanks a lot, asshole.

For an audience that grew up with job stability and that sense of caring, this must have been horrifying, and with good reason: this film happened just before the explosion of the portrait of the greedy company in the 1980s. It’s fitting that we get this theme because it signifies the shift from that warm, fuzzy employer to the one that cared more about the profit than the people. The crew of the Nostromo is a mining operation, with 20,000,000 tons of mineral ore aboard upon its return to Earth – they signed up for a mining job, complete with hypersleep and a specified time frame. So when they have to follow protocols regarding extraterrestrial life, they do so, but they’re not happy about it. Then they’re asked to do more: bring aboard someone who has been exposed to a dangerous organism, potentially placing them in harm’s way. Then they’re forced to watch a friend and fellow crew member die painfully. This clearly crosses the threshold of what your employer can ask you to do. And yet, we all learn at the same time that the company truly does not give a shit about its employees, who have entrusted them with their safe return. They are considered expendable; the alien is a far better investment than human life. Ash even praises it with his admiration, picking favorites with absolute certainty. As an audience, this scares us. We work hard. We give up our time away from families, friends and interests to make money, and at the end of the day, many of us expect to be able to clock out without having to devote our entire lives to work. There has to be that work-life balance, and Alien shows us the nightmare side of that coin: the company that demands a bodily sacrifice in the name of its success. No matter what you do, it’s no good unless if the company meets its objectives. Even if you have to die in the process.

File this under “not in my job description”…

To this extent, there’s a disturbing piece of filmmaking that has stuck with me for years. It’s not enough that Lambert is cornered in inevitable death. The alien’s pointed tail snakes between her open legs as she stands face-to-face with it. The speared tail moves upwards toward her ass. We see her scream in pain. That’s a pretty nasty inference right there, and we all get it: this woman is getting sodomized with a spike. It’s not enough that she’s got to die; hell, it’s not even enough that she’s got to get ripped open and made dinner. Nope. She has to get a spike shoved up her ass. If that’s not a metaphor for the rim job this company is pulling on its resources, I don’t know what is. She can’t even die quickly; she has to be violated painfully before she’s allowed her unwilling death, something that an executive signed off on somewhere. It’s easy for someone else to shuffle the papers; she’s the one cashing the cheque.

That’s really what it comes down to: the person who cashes the cheque is treated as property of the company, and the company gets to decide how to handle its resources. In this respect, Weyland-Yutani owns you. And that’s the most terrifying part of the film. It’s not the alien. It’s not the notion of being alone in space. It’s the idea that your employer controls everything about you once you decide to work for them. Right down to your last breath.