The Keeper of the Tales: The Need for Embellishment in Big Fish

So for the past three years, I’ve been trying to cover Big Fish in time for Father’s Day. Each year, I’ve failed. Hard. I have failed so miserably. I’m like that mom that keeps telling herself she’s going to decorate this elaborate birthday cake for her child’s big day with the help of Pinterest, fucks up the fondant figures spectacularly, then must rush to Wegman’s in a hurry to buy a cake and have someone scrawl, “Happy 8th Birthday Jayden” on it 20 minutes before the party starts. Sounds like it sucks? Yes. It does. And I own that. Which leads me to the bigger point of Big Fish: it’s a film about the mundane lives of ordinary people who are special in their own right. It’s about the necessity for the grandiose in a lifetime of the ordinary. And we need that.

I won’t lie, this is a pretty accurate representation of life as the short chick.

Big Fish sees a clash between two parties: father Edward (Albert Finney and Ewan McGregor), a salesman with many larger-than-life stories, and Will (Billy Crudup), his reality-grounded son. While Edward spins huge yarns about parachuting into enemy territory during the Korean War, working at a circus, and catching a massive catfish with his wedding ring as bait, Will quietly resents the frequent time away his father spent from him, as well as his inability to just be truthful for once. We’re presented with both sides of the coin: Edward’s version of events, and then Will’s attempts to uncover the truth about his father’s exploits, as a way to discredit – and uncover the truth about – the man before he dies. Along the way, Will is surprised to learn that his father’s life was indeed pretty adventurous, and he simultaneously lived this life of escapades while remaining sexually and emotionally faithful to his wife.

Time literally stops for this guy.

Most touching is the fact that, when written on paper, Edward’s life reads like so many others in his generation. He traveled around for a bit after school. He met a woman and fell in love. He got drafted to go to war. He became a salesman. He had a friendship with a woman, and his son suspected an affair. He later encountered illness and met his end at a hospital. On paper, Edward is like so many of his contemporaries. He’s not special. There’s nothing in those sentences above that suggests he was anything more than a cog in a much larger machine, which is a pretty depressing thought. After all, who wants to be boiled down to just a few sentences that bear a strong resemblance to everyone else?

Pretty, but typical.

However, Edward possesses the ability to tell a story and inject just a little bit of magic into his life, which is what separates him from the rest of the world. The most significant story he tells is that of the catfish. The catfish pops up twice: during the birth of his son and at the end of his life. The first instance sees the catfish being caught, while the second sees Edward becoming the catfish upon his death. In this respect, the catfish represents the desired legendary nature of the soul: it’s the legacy of being an individual that’s the subject of a tall tale that will be passed down. During the birth, it’s something he catches – it’s the moment of pride, something his wedding ring has afforded him, and something that will be retold and associated with his child; it’s the celebration of a huge moment by equating his child’s birth to a larger-than-life event. Upon his death, he becomes the fish himself, something his son will then pass on to his own child. The fish is the cycle of remembrance and deep emotion – it can swim the waters in all their depth and remain a tale of wonder. Instead of just being a man who happens to have been like so many others before him, Edward is now special. He’s the big fish everyone remembers, not some name written on paper.

Gotcha!

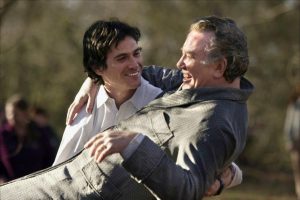

It’s in this spirit of specialness in the face of a pretty milquetoast existence that separates Edward from his contemporaries and grants him the ability to stare his own death squarely in the eye (quite literally, at one point). By shaping the stories that will define the memory of him as a person, he becomes the author of his own narrative. Pure fact isn’t the sole deciding factor anymore – Edward lets public perception of his exploits shape who he is and how he is remembered. As such, Will tells him as he narrates the story of Edward’s death, “And the strange thing is, there’s not a sad face to be found. Everyone is just so glad to see you.” Edward can die happy because this is the story that will be passed down. No one will talk about the boring parts; no one will mention that he died in a hospital bed a sickly old man. Edward becomes the subject of tall tales that get passed down so that those who come after him get some magic too. And let’s face it, we all love a good story: it fascinates us as children to think of our loved ones as these superheroes because they’re our world, and when they’re gone, it gives us a smile to recall one of those epic adventures.

I’m not crying. You’re crying.

Big Fish is thus the story of embracing the transformative power of a story. It’s taking the power back from a world that wants us to be common, to become more than just words on a page: it’s the magic of the orator, the wonder of an open mind, and the inspiration drawn from the little moments of magic we all possess in our own lives. We all have the ability to become a big fish like Edward. We just have to find those that understand the need to dream in the face of a boring everyday existence, and the joy in embracing the cycle of death when it’s time to take the final bow.