Captains of Industry: Citizen Kane (1941) and The Art of the Troll

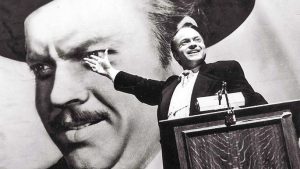

Citizen Kane (1941) is one of those films that continually receives acclaim with good reason: it’s gripping, it’s well-acted, and it’s expertly directed by writer/director/producer/star Orson Welles. Welles drew inspiration for the film’s main character, Charles Foster Kane, from several different public figures: utility and railroad magnate Samuel Insull; Harold Fowler McCormick of the agricultural McCormicks; and William Randolph Hearst, famed newspaper magnate and all-around asshat. Welles managed to piss off quite a few wealthy heavy hitters, and in doing so, became a long-term hero for the masses.

MEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE.

A quick recap of the film: a reporter attempts to unravel the life of late newspaper publisher Charles Foster Kane, whose final word – “rosebud” – left everyone baffled (including this filmgoer, who wondered how in the hell the last word of a man who dies alone is heard and reported. He wasn’t screaming “rosebud” from his bed.). Kane came into money through his mother, whose goldmine was used to set up the youngster with an education and enough capital to get his tabloid newspaper started. Kane moves from news to politics, and loses his political career when he’s caught having an extramarital affair with Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). Susan, an aspiring opera singer who can’t sing, marries Kane and is forced into an ill-advised opera career that sees the spiraling of her happiness, health and romantic relationship. Divorced and alone, Kane dies without a soul nearby (but somehow we know the last thing he said was “rosebud”) and the mystery of his final word is solved only by the audience: rosebud is his childhood sled, a memory of happier, uncomplicated times.

“Get me Miss Cleo for the Horoscopes section.”

Back to the influencers. The character Kane was a composite of Insull, McCormick and Hearst, with some splashes of Welles himself thrown in there. Insull died in debt after a financial scandal that left many, many people very, very poor (really, he was arrested on antitrust violations and there was legislation put into action because of this guy). McCormick was a wealthy man who ditched his wife for Ganna Walska, a woman who couldn’t sing; he championed her career and looked like a fool for doing so. But Hearst was the one who took the largest personal burn to the incorporation of his life’s details. Hearst put up every roadblock he could on the film, and not just because he was upset with the parallels to his newspaper ties – he was livid at the comparisons of Kane’s second wife, Susan, to his own mistress, actress Marion Davies. The Davies stuff was quite scandalous back then, as Hearst’s wife refused to divorce him so that he could marry his mistress, whom he stayed with until his death. The real juiciness came from the insult Hearst took to the character Susan – as a producer of Davies’s films, the implication is that he was carrying the work of a crappy actress. Once people figured out that Hearst was knocking boots with Davies, her artistic credibility was shredded and he became a punchline. Furthermore, the rumor persists that the word “rosebud” was his own personal name for her clitoris. Which… the implications are bad on that one. When the main character who bears a strong resemblance to you dies alone, thinking about his happy place and that turns out to be your nickname for your girlfriend’s snatch, I’d be mad too.

How do you spell “obvious” again?

However, the thing that persists is the fact that Welles insisted that it was a composite piece – a man who stirred the shit so beautifully it nearly cost him his career. The beauty of it is that Hearst took the whole thing as an attack on him entirely and made it his mission in life to sabotage Welles’s film. It worked for a bit, but then those pesky French fell in love with the damn thing, and soon everyone was talking again about how clever of an artist Welles was, and how Hearst was such an ass, and by the way do you KNOW what he calls her vadge? Truly, Hearst was the one on the defensive: Welles went to great lengths to say that Marion Davies was a wonderful woman and a talented actress (emphasis on the talented actress part), and so the character Susan couldn’t be her because oh yeah SUSAN WAS BASED ON GANNA WALSKA. The result: Hearst looked like a whiny crybaby who couldn’t stand that people talked about him because he was a rich, powerful newspaper overlord. Hearst was used to calling the shots, and he couldn’t take knowing that people were laughing at him. Talk about a fragile ego.

Cry into the expensive booze, Susie.

I can’t help but love Welles for the lasting impact of this, because he effectively strips the power away from a man who thought everyone had to bow down to him. Sure, Hearst had money, but he also screeched and threw tantrums because he thought that some snot-nosed theatre punk was picking on him, and no one could dare question the life of someone as important as him. And sure, Welles went on to a life of alcoholism, but he managed to give us arguably the greatest film ever, as well as the absolute best outtakes from wine commercials. As for Hearst, he gave us a raw deal on the hemp industry that resulted in environmental damage, yellow journalism and Patty Hearst. There’s a clear winner long-term.