Give Me Liberty Or Give Me Death: Female Rebellion in Tag (2015)

Gender perspective is an extraordinary thing: what men see in a film is totally different from the themes a woman picks up on, which makes for some interesting conversations. Such is the case with the Japanese import Tag (2015), which starts off famously with an unseen force cutting people in half and winds up following three very different women as they’re chased through a normal-yet-hellish landscape. The men I know see some batshit action-ish movie with an overt ending, but the women I know… oh do we see something else entirely. In particular, we see destiny and the patriarchy, and how much we’d like to escape a pre-programmed world.

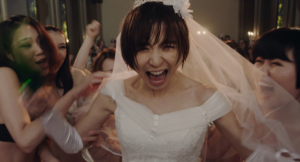

Live footage of me at the end of the day.

The three women we encounter in the film have similarities, despite the differences of their scenarios. Schoolgirl Mitsuko (Reina Triendl) is shy and quiet on her school bus, choosing to write quietly while her classmates are having a sexy schoolgirl pillow fight; she then must run for her life from the unseen force that rips everyone in half, and faces off against a schoolteacher who mows down the students trying to help her. From there, she jumps into the reality of Keiko (Mariko Shinoda), a bride who is forced down the aisle to marry a pig while her underwear-clad classmates laugh at her; she must stab her way through the church with a broken bottle to escape. In the third installment, Mitsuko experiences life as Izumi (Erina Mano), a top runner in the middle of a race, again with the same classmates and wedding guests from earlier in the crowd; she’s then attacked by a classmate who tells her that if she’s alive, everyone else dies. Each time, our heroine is subjected to the laughter and/or jealousy of her female peers; she is the virtuous-looking one that stands out in a sea of enticing women; she’s told that she must die so that everyone else can live.

It’s okay to scream. This scenario sucks.

What’s most damning is what comes next: Mitsuko finds her way out of the game she’s been trapped in for the past 150 years, called Tag. She lands in a grimy place called The Man’s World, populated by gamers in their underwear who play a 3D horror game in which hot babes are killed in spectacular, over-the-top fashion. It turns out that she was cloned without consent by the game’s creator (Takumi Saitoh) to recapture a classmate he idolized but never had a chance with which to have a relationship. When confronted with her final destiny – to engage in sex with a simulation of the creator as a young man while the older version watches – Mitsuko chooses to reject the younger version of the man, then coordinates suicide in each instance of the game to achieve freedom.

When given the choice…

Oh where to start. The film wears the theme of women not wanting to be treated like toys on its sleeve, and that part is extraordinarily blatant in its delivery. The subtlety here lies within the symbolism of each woman. Mitsuko is an innocent yet sexualized schoolgirl: she’s the virginal sweetheart of the game’s creator, with the express purpose of finding her way to him so that he can engage in sex with her, telling her, “Surrender to your destiny.” Keiko is being forced to marry a pig, which… if that’s not a statement on the expectation of an unkempt man demanding to marry a perfect, pristine woman way out of his league, then we’ll need to re-examine the definition of “symbolism”. Then there’s Izumi: the perfect runner with natural talent, that must die so that the mediocre women around her can live. Her existence is viewed as a boon for them because she’s so much better, making them look like nothing by comparison – it’s supreme jealousy and competition. In each instance, these women are told to accept things the way that they are: give in and have sex with the man who manipulates you; marry the pig because that’s your only option outside of pain and death; be average in your abilities so that no one else feels threatened. If that sounds like a lot, most women refer to those messages as “days that end in ‘y’”.

Most days feel like this.

However, the most damning piece of the ending comes from the notion of fate and how to trick it, especially with overtones of being female in a male-created world. The creator sneers at Mitsuko, “I bet you couldn’t have imagined that your DNA would be used for our entertainment.” That statement reduces her role to that of nothing more than a slave: she doesn’t have rights or wants or desires – her sole purpose is to entertain, even if she doesn’t wish to do so. She’s informed that her purpose is to entertain based upon harvested DNA, making the situation into a cloned servitude of both sex and emotional sacrifice, as she and her counterparts are routinely brutally murdered for sport and implied sadistic sexual gratification against their consent. These systems persist due to their overwhelming prevalence and lack of rebellion. Mitsuko’s salvation from this scenario comes from her friend, Aki (Yuki Sakuraki): “But you can trick [fate]… Do something spontaneously that you’d never do. … Do something unexpected without awareness. “ This statement empowers Mitsuko to rebel against her fate of being a sex toy to a giant creep with access to sophisticated technology. In addition to this rebellion, she and the other counterparts of the game commit suicide simultaneously. Rather than accept her role in a world designed for male entertainment via sex, violence and submission, she chooses stabbing herself to death. And each time, the reaction to the end of the film runs the same along the gender lines:

Men: Wow, that’s a little extreme.

Women: Fuckin’ PREACH SISTER!

Don’t they look pleased as punch to see you.

Therein lies the difference between a group that doesn’t have to deal with this lens as their reality every day, and those that do. The female experience is messed up: we’re tasked with being the pleasure centers, the care givers, and the entertainment without much thought lent to if we even want to be there in the first place. Some of us don’t want to play Tag – some of us just want to stay at home and read a damn book or play a zombie game. We’d rather not have to choose death over being the plaything of a creep, but, you know, it’s 2018 and a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do.