Letting It All Hang Out: The Male Form in Bronson

About five minute into Nicolas Winding Refn’s Bronson, I felt like I owed Tom Hardy a drink. Anyone who is naked that much in front of me deserves alcohol at the very least. As Charlie Bronson, Hardy was naked multiple times throughout the film. This isn’t scandalous to me – it’s just different for someone from America, a place where all nudity has to be sexualized and sensationalized for optimum press coverage. To Refn’s credit, though, this never once came off as something sexual. In fact, it could be argued that Refn used Hardy’s nudity in the film to convey two main points: praise of the male form, and the absolute dedication to battle as a central piece of the character’s identity.

For a film about Britain’s most violent prisoner, this film did not have much sex in it. The connotations of filmmaking in the modern age have lent a symbiosis to sex and violence: the two are often feed off of each other in a pairing that functions more so as a bid to gain strength and dominance over the storytelling. Typically, this is achieved through the objectification of women, particularly in crime dramas: the women are there for sex, silencing or saving, on full display physically and not saying much. The interesting piece is that we don’t really get female nudity in this film but on one occasion: when Hardy’s Charlie walks into a strip club and sees a topless dancer gyrating in front of him. And sex? We get that one time only as well: when Alison (Juliet Oldfield) and Charlie are having sex in a bit of a montage/transition moment from one piece of action to another. This isn’t a graphic act: we hear the moans and see the outlines of our two actors, but we’re not up close and personal, as the scene is lit in dark blue shades that obscure our view. We’re not given any gratuitous nude shots of either Oldfield or Hardy – they’re tilted in such a way that makes it hard to make out any nakedness. It doesn’t rule nudity out entirely – quite the contrary, Hardy strips down quite a bit in this film, totally defeating that point. Refn, though, takes pains to make sure that Hardy’s naked body isn’t sexualized. This is a pretty nifty feat, as we consider that Hardy is what many would consider conventionally attractive: he’s got pillowy lips, sad eyes, and in this film, muscles for days. We should want to see this guy naked; as an audience, we should want to jump his bones. However, Refn makes sure through this omission that Hardy’s naked body isn’t there for that purpose.

Underwear does not count as nudity.

What he is there for is the function of fighting machine, to which our attention is turned so that praise may be lavished. Any time that we see Hardy in a state of nudity, he’s engaging in battle. This is where Refn wants us to focus on the male form: not when he’s having sex, not when he’s walking down the street, not when he’s wearing the hell out of a suit, but when he’s about to brutally attack someone. There’s a distinct line drawn between the clothed guards and the naked Charlie: the guards require multiple men to take down and beat the prisoner, while Charlie bounces up and fights with the ferocity of a provoked tiger. Strength is therefore associated with a lack of clothing: he may have blood streaming down his face at the end, but he’s given way better than he’s gotten, and without the use of helmets and billy clubs. We get lighting that enhances this state, from reds to oranges to sickly greenish-blue overhangs, bathing him in an unearthly glow, as though his prowess is unnatural, despite that he’s in an au naturel state. In time, we even get to see the naked Charlie decorated, ranging from black paint to slick lubricant in order to give him an advantage against the guards. In fact, the scene in which Charlie is being greased up by his prison librarian hostage is telling: he’s barking orders at the scared man, who seems terrified that he’s going to be beaten or killed at any moment. Charlie commands him to rub his body down, dictating location (first the back, then his ass) and speed, insulting the man’s abilities by referring to him as homosexual. Let’s be clear, though, that this act is in no way sexual. It’s not a turn-on for anyone, despite that we’re getting full frontal nudity here. Nope. We’re staring and wondering what kind of damage this guy is going to inflict upon the guards. There’s nothing scandalous or blush-worthy in that moment. This isn’t a guy with a raging hard on that’s about to perform for us. This is someone who is about to charge naked into battle, completely mad and willing to rip to pieces anyone who stands in his way.

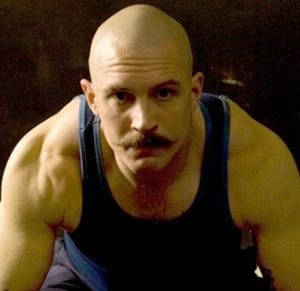

Muscled intensity.

This is significant because it removes all desire and attraction from nudity, which we’ve been programmed to immediately associate with sex. Where does that leave us? Simple: we get to appreciate the male form, which is something still relatively new in cinema. The female form is easy: we’re bombarded by constant images of beautiful, naked women. We get that ideal loud and clear: full, large breasts; rounded hips; thin arms and legs. There’s even a battle being waged now for the right length of female pubic hair, ranging from tamed grooming to fully waxed. For men, we have gotten an ideal (tall, flowing hair, muscles, etc.), but it’s always been held back from full frontal nudity for American audiences. There’s the concept that men’s bodies somehow are not sexy and that no one wants to see male genitalia onscreen, which, if you break it down, is sexist because it demeans an entire gender as unattractive, serving the sole purpose of providing pleasure while the other half of the equation gets to look pretty (note: this isn’t taking into account same-sex attraction – otherwise, we’d be here forever, as the complexities of eroticism in gay cinema is a subject that deserves its own post). Personally, I love the male form as much as the female form, and so I think it’s terrible to put the ideas into guys’ heads that they’re inherently ugly. In the case of Bronson, though, we get male nudity as a way to appreciate the fighting form. The greasing before the fight reminded me a bit of the rituals employed pre-competition for the athletes of Ancient Greece, which set the bar high in terms of what they considered physical perfection; at that point in time, athletes competed naked not so that they could be held up as lust-worthy objects, but because their physical conditioning meant that their dedication to the sport in question deserved recognition as the apex of physical form. In a sense, this made the act of appearing naked in public a point of bodily pride: you worked hard for that body, and everyone was expected to marvel at it in action. This was its purpose once it reached its potential. There are arguably two purposes of the male body: to reproduce, and defend and protect. The latter principle is applied to Hardy’s nudity in Bronson: he’s not there to sex us up; he’s there to show us what a fighter in top form looks like. It’s not shocking when we see a man fully nude on screen – it’s a chance to anticipate his next move, and appreciate the form in a way that the female body is not typically appreciated: in a non-sexual, optimal use form. It’s the chance to take a look at what a male body can do once everything is stripped away from it, without the hassel of sex involved.

A beautiful image untaintd by sex.

Ultimately, the act of being naked does more for the character as we get to know him as an audience. If you notice, he’s fully clothed on stage as he’s narrating the action from time to time. This is supposed to give us a glimpse into his head, a chance to get to know the real Charlie. However, that’s not the real Charlie – we may learn that his actual first name is Michael, but that’s just a name, a label that he feeds us. Words are useless, as he can tell us anything he wants. To glimpse who he is at his core requires us to witness him fighting prison guards naked. He needs to strip down and bear the intensity of a fighter, and we need to stop and stare at him because this is who he is; he is not going to change, and this is the best expression he has. The true intimacy is the face he displays, not the words he feeds us. Therefore, we have to get a good, long look at his naked body in action in order to really understand the man in front of us. And that right there deserves a slow clap, because it’s not easy to take a conventionally attractive man, get him oiled up and naked, and still refuse to look at him in a sexual manner.

I really didn’t expect to spend my weekend writing about Tom Hardy’s naked body. Like the meaning I found in this film’s nudity, it took me by surprise. I’m looking forward to seeing if Refn can do the same thing with the female body. That, however, remains to be seen.

Pingback:Trailer Tuesday: Molly’s Game – The Backseat Driver Reviews