The Positive of Fear: Goosebumps and the Need For Children’s Horror

I have one, if not two, budding horror hounds on my hands. My eight-year-old adores Five Nights At Freddy’s. My ten-year-old has been happily consuming older horror flicks from the 1930s. I have multiple friends that have told me I’m raising my children right. Here’s the thing, though: I don’t think what I’m doing with them – fostering a love of horror – is necessarily bad nor exceptional. I mean, I was one of those horror movie nuts from a young age; the apples didn’t fall far from the tree. The simple fact is that kids love to be scared. This explains the popularity of things like FNAF, as well as the recent summer hit Goosebumps. In fact, Goosebumps typifies why kids need horror: through the lens of the fantastical, children can explore the real-life horror that await them as they age, making the faculty of imagination and combat of evil a necessary life skill.

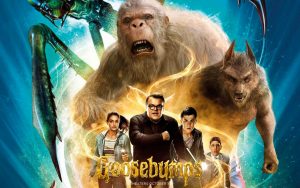

Gotta love it.

Goosebumps starts off with a some light-hearted yet heavy material. We meet Zach (Dylan Minette), a kid who has just relocated from New York City to a small town in Delaware. Zach has not had an easy time: his father has passed away, and per his mother, he’s taking the loss rather hard: shutting himself in his room, refusing to talk about the death or how he’s feeling. Losing a parent is tough on an adult; it’s fucking horrifying for a child, especially a 16-year-old boy that is trying to navigate young adulthood without a role model. Adding to this dynamic is the fact that Zach – who already feels isolated – is not only the new kid at school, but the son of the new, dorky, trying-hard-to-be-hip vice principal. His new friend Champ (Ryan Lee) points out that she’s awkward, which says a lot considering that Champ is the resident geeky outcast. Toss in his aunt Lorraine (Jillian Bell), a woman with no mind-to-mouth filter that thinks a fun night with her nephew involves bedazzling clothing while talking about her poor excuse for a love life, and this kid’s life is an exercise in discomfort and feeling out of place. I feel for Zach; his life at the moment is a transition that no one wants to endure.

So when Zach gets to the adventurous part of the story, we perk right up because the monsters he faces are so ordinary that there’s a chance we might face them in a flight of fancy. He gets to face a fairly impressive list over the course of the film: the abominable snowman, an invisible boy, a giant preying mantis, a werewolf, and evil garden gnomes to name a few (and right now, I’m picturing an evil David the Gnome, and it’s destroying my childhood). These are all things that go bump in the night, in which most children believed in their youth. Zach isn’t that far removed from childhood, so it makes sense that the monsters are not the terror-fest that an adult would see. Zach isn’t battling a vampire whose face opens to display rows of teeth, nor is he battling Cthulhu for control of his soul. Nope. He’s slugging his way through a kitchen, dodging knives and plates thrown at him by creatures that can regenerate – garden gnomes, no less; something ordinary that has suddenly changed from benign to malicious.

The grocery store: horror at its finest.

And therein lies the beauty and meaning in horror for children: kids need to learn how to confront the ill in the world in a manner that is ordinary yet reassuring of their own abilities to persevere in the face of adversity. Stine (Jack Black) references this in his explanation of the creation of his stories: “When I was younger, I suffered from terrible allergies that kept me indoors. And all the kids threw rocks at my window and called me names. So I created my own friends. Monsters, demons, ghouls to terrorize my neighborhood and all the kids that made fun of me. And they became real to me. And then one day, they actually became real.” Allergies, people – ALLERGIES is the root cause of everything that happens in this film. One kid got made fun of for being indoors due to severe hayfever, and that managed to spawn dozens of monsters for our Everyman to fight. This lesson is two-fold: use your mind to create something when you are lonely, and use your brain and inner strength to fight back when the world around you turns monstrous. The possibility for the world to suddenly turn scary is very real in everyday life; by translating this into a scary situation for children, who then have the guts to step up and save the day, children learn that they too can have this same strength. It’s fun to think that you can battle an evil puppet and live to tell the tale; it’s fun to think that you could be that hero that saves the school. And in the end, our subtle lesson for Zach resonates with the kids watching the film: Zach was able to defeat the monsters, and suddenly was not afraid of the new changes surrounding him. He’s proud of his mom, he’s happy to have Champ as his new best friend, and starting over in a new place isn’t so bad. He kicked the abominable snowman’s ass – a new locker and lunchroom is a piece of cake. Once you face something like that, your life isn’t so terrifying by comparison.

We’re in this together.

Horror for children accomplishes this very goal: it creates something that can be overcome, something that is sublimely scary and age-appropriate, and functions as a coping mechanism for a child undergoing a transition. It may be a move, it may be a shifting family dynamic, it may be a learning disability. The lesson, though, remains clear in films like Goosebumps: your life is not so bad, and you are good enough to be part of the solution in a scary situation. Horror teaches our kids that they’ve got this, and that makes for an adult that can handle the very real punches that life can throw.